Fiction

Tales and the tradition for storytelling.

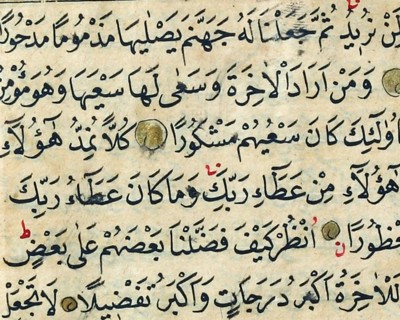

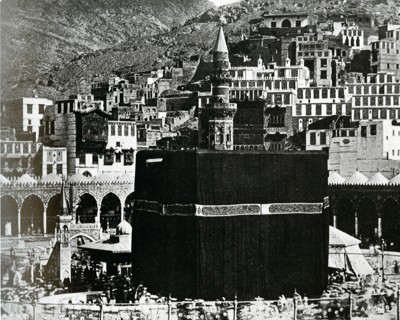

The earliest Islamic literature, including fiction, was written in Arabic. The starting point was Bedouin poetry created on the Arabian Peninsula around the time immediately preceding the Prophet Muhammad. Here the storytellers seated by the desert campfires gave form to what would become the first written poems, and it was they who passed on the narrative tradition which became the springboard for the rich Islamic fiction that followed later.

Particularly prominent among the earliest forms of poetry was the long poem, the qasida, comprising some hundred couplets whose subject matter often centred around old camps, youthful love and legendary hunts. However, other and shorter narratives were also written in verse at the time, such as ascetic poems, drinking songs and hymns celebrating the realm of the erotic. The court poet of Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786-809), Abu Nuwas, was particularly well known for the latter.

As the art of poetry evolved, a number of very short poem types – such as the rubaiyat, a quatrain form with four couplets (especially associated with the poet Omar Khayyam) and the ghazal, comprising some seven to fourteen couplets – grew increasingly prominent. Such concentrated and lighter forms became favoured among the great Persian poets, Nizami, Rumi, Sadi, Hafiz and Jami. They were used to describe the myriad ways of love, not least the longing for ‘the Beloved’ – who could also be understood as God. A clear duality could be traced in the poems’ metaphors of love, especially in the mystic poems of Sufism.

Writers found mutual inspiration in terms of content as well as form through exchanges that cut across the Islamic countries. The Persian-born court secretary of the Arab Abbasid Caliphate, Ibn al-Muqaffa, translated a number of Persian narrative works into Arabic as far back as the eighth century. The best-known example is the Kalila wa Dimna, originally an Indian book of animal fables that was also a ‘mirror for princes’ (a textbook of counsel and wisdom for rulers). Ibn al-Muqaffa’s clear and simple language later became a model for Arabic artistic prose.

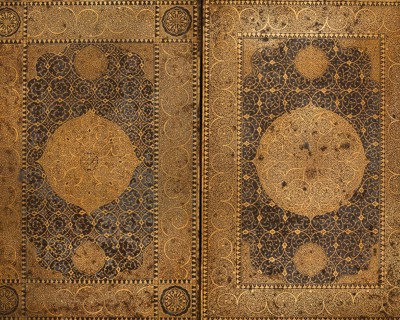

From the tenth century onwards, historical legends from the East and the West were recorded in Iran. Magnificent manuscripts – later versions were further embellished with illustrations – were produced in response to a growing demand for entertainment and information. A unique volume in this context is Firdawsi’s vast epic Shahnama (Book of Kings), comprising 50,000 couplets devoted equally to mythology and regular history.

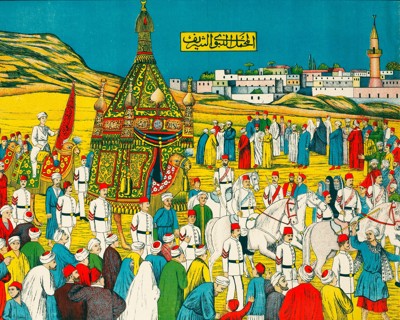

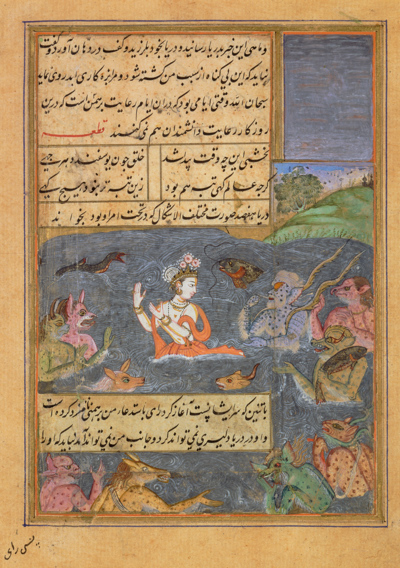

India’s and Turkey’s contributions to the literary history of the Islamic world were made especially from the sixteenth century onwards, primarily taking the form of the regions’ historical legends and myths. The popular tales about the folk hero and trickster Nasreddin Hodja spread from Turkey, and the Hindu legends, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana and the Tutinama, were translated in Mughal India. The latter was done at the behest of the curious and tolerant prince, Akbar.

Arabian Nights, also known as One Thousand and One Nights, is probably the most famous work from the Islamic world today (not least in the West). It offers an illuminating example of the often complex and wide-ranging genesis of the rich and diverse Islamic literary fiction. When, in eighteenth century Istanbul, the French diplomat Antoine Galland collected material for a modern version of the work, he came across stories that had been retold for centuries, if not millennia, from easternmost Asia to westernmost North Africa.