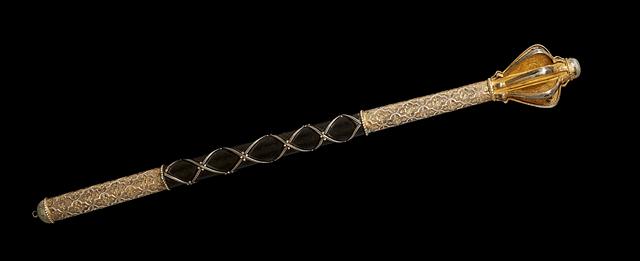

Dagger of steel, gold and walrus ivory

Blade: Turkey, Istanbul; second half of the 16th century. Hilt: Presumably Turkey; second half of the 16th century or 17th century

L (dagger): 34.2; L (hilt): 11.5 cm

Inventory number 14/2022

Like item 8a-b/2022, this dagger belongs to a group with straight or slightly curved blades. Some are pierced by openwork and/or have areas in raised relief, others do not, but a trait characteristic of all of them is fine gold inlays. A number of the daggers have survived intact, but many have been given new hilts over time.

Several of these daggers have previously been identified as Iranian,1 while more recent publications generally attribute them to the Ottoman Empire in the century after Selim I’s victory over Shah Ismail in the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514.2 As a consequence of the defeat, many Iranian artists were relocated to Turkey. Scholars have not yet established a clear-cut chronological sequence among the approximately thirty preserved specimens.

The straight blade of this dagger features openwork as well as cartouches in relief, and both sides have gold inlays in the form of various foliar arabesques and nastaliq inscriptions in Persian. However, Persian was the dominant language at the Ottoman court, and the dagger which, in terms of decoration, is most reminiscent of 14/2022 has both Turkish and Persian inscriptions. This suggests a Turkish provenance.3 In poetic form, the verses address not only the dagger’s ability to take life, but also the deadly effect of all-destroying love.4

The hilt has rudimentary quillions, which on more elaborate examples terminate in dragon heads, and the slightly twisted grip, seemingly shaped like bundled branches terminating in a rounded pommel, is reminiscent of that of other daggers in this group.5 The fact that the upper, undecorated part of the blade is exposed proves that the hilt is a later addition. It has previously been suggested that the hilt may originate from India, but the fact that it is made from walrus ivory suggests a Turkish rather than an Indian provenance.6

Several of these daggers have previously been identified as Iranian,1 while more recent publications generally attribute them to the Ottoman Empire in the century after Selim I’s victory over Shah Ismail in the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514.2 As a consequence of the defeat, many Iranian artists were relocated to Turkey. Scholars have not yet established a clear-cut chronological sequence among the approximately thirty preserved specimens.

The straight blade of this dagger features openwork as well as cartouches in relief, and both sides have gold inlays in the form of various foliar arabesques and nastaliq inscriptions in Persian. However, Persian was the dominant language at the Ottoman court, and the dagger which, in terms of decoration, is most reminiscent of 14/2022 has both Turkish and Persian inscriptions. This suggests a Turkish provenance.3 In poetic form, the verses address not only the dagger’s ability to take life, but also the deadly effect of all-destroying love.4

The hilt has rudimentary quillions, which on more elaborate examples terminate in dragon heads, and the slightly twisted grip, seemingly shaped like bundled branches terminating in a rounded pommel, is reminiscent of that of other daggers in this group.5 The fact that the upper, undecorated part of the blade is exposed proves that the hilt is a later addition. It has previously been suggested that the hilt may originate from India, but the fact that it is made from walrus ivory suggests a Turkish rather than an Indian provenance.6

Published in

Published in

Tony Curtis (ed.): The Lyle official arms and armour review 1976. Galashiels 1975, p. 31;

Islamiske Våben i dansk privateje = Islamic arms and armour from private Danish collections, Davids Samling, København 1982, p. 110.

Kjeld von Folsach, Joachim Meyer, Peter Wandel: Kamp, jagt og pragt. Våben fra den islamiske verden 1500-1850, Davids Samling, København 2021, cat. 133, p. 248;

Joachim Meyer, Rasmus Bech Olsen and Peter Wandel: Beyond words: calligraphy from the World of Islam, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2024, cat. 67, p. 211;

Islamiske Våben i dansk privateje = Islamic arms and armour from private Danish collections, Davids Samling, København 1982, p. 110.

Kjeld von Folsach, Joachim Meyer, Peter Wandel: Kamp, jagt og pragt. Våben fra den islamiske verden 1500-1850, Davids Samling, København 2021, cat. 133, p. 248;

Joachim Meyer, Rasmus Bech Olsen and Peter Wandel: Beyond words: calligraphy from the World of Islam, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2024, cat. 67, p. 211;

Footnotes

Footnotes

1.

Kjeld von Folsach, Joachim Meyer, Peter Wandel: Fighting, Hunting, Impressing. Arms and armour from the Islamic World 1500-1850, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2021, p. 248 suggests that the hilt may be of Indian provenance.

2.

See for example A. Ivanov: ‘A group of Iranian daggers of the period from the fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth, with Persian inscriptions’ in Robert Elgood (ed.): Islamic arms and armour, London 1979, pp. 68 and 69.

3.

A. Ivanov: ‘A group of Iranian daggers of the period from the fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth, with Persian inscriptions’ in Robert Elgood (ed.): Islamic arms and armour, London 1979, pp. 64–77.

4.

See for example Holger Schuckelt: Die Türckische Cammer, Dresden 2010, p. 140.; David G. Alexander, Stuart W. Pyhrr and Will Kwiatkowski: Islamic Arms and Armor in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2015, pp. 196–199; and Catalogue of Arms and Armour from India, Iran and The Ottoman Empire, The Wallace Collection (pending publication).

5.

A. Ivanov: ‘A group of Iranian daggers of the period from the fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth, with Persian inscriptions’ in Robert Elgood (ed.): Islamic arms and armour, London 1979, pp. 64–77. The dagger is at the Wallace Collection OA1430. Here it has been dated as hailing from the second half of the sixteenth century.

6.

See Kjeld von Folsach, Joachim Meyer, Peter Wandel: Fighting, Hunting, Impressing. Arms and armour from the Islamic World 1500-1850, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2021, pp. 279–280.

The Ottomans

Mace head, silver and silver-gilt, chased and engraved; wooden handle covered with leather

Wicker shield wrapped with colored silk and metal threads and with an umbo and metal fittings of steel and brass

Powder horn, silver, with coral beads and the original hanging

.-The-David-Collection_Copenhagen_photo-Pernille-Klemp.jpg)

Short sword (yataghan) of steel, rhinoceros ivory and gold with scabbard of wood, textile, gold, and silver

_-Photo-Pernille-Klemp.jpg)

.-The-David-Collection_Copenhagen_Photo-Pernille-Klemp.jpg)

_-Photo-Pernille-Klemp.jpg)

_-Photo-Pernille-Klemp.jpg)

.-The-David-Collection_Copenhagen_Photo-Pernille-Klemp.jpg)