Sabre (tulwar) of steel, iron, copper and gold

India, Delhi or Awadh; The blade 1163 H (1749–1750); The hilt probably 2nd half of the 17th century

L: 95.5; Hilt L: c. 17 cm

Inventory number 25/2021

The blade of this sabre is made of watered crucible steel, also known as wootz steel. The inlaid gold inscriptions state that it was commissioned by Safdar Jang Bahadur and made by Muhammad Baqir Mashhadi in 1163. At the time of writing, there are nine known published sabres with almost identical inscriptions, of which six are fitted with shamshir hilts and three with tulwar hilts.1 They were forged while the Persian-born Safdar Jang was nawwab of Awadh and vizier to the Mughal emperor Ahmad Shah (1748–53), but whether the likewise Persian-born Muhammad Baqir produced them in Delhi or in one of the cities of Awadh is not known. Indian weaponsmiths did not usually sign their blades, whereas the practice was more widespread in the Iranian and Ottoman realms. Whether the sabres were intended for Safdar Jangs guard or as gifts is also a matter of conjecture.

The characteristic, Indian tulwar hilt is dominated by a large pommel disk. This one has a tang nut, to which an eyelet with a wrist strap would originally have been attached. The swelling grip joins the short guard and the langet in forming a cruciform shape. The entire hilt, which is made of iron, is inlaid with flowers, stems and leaves as well as carefully delimited lines of gilt copper raised in relatively high relief. Some tulwars also feature protective hand guards. Stylistically, the hilt appears older than the blade. Replacing parts of sabres and daggers over time or reusing old ones was a common practice.

The characteristic, Indian tulwar hilt is dominated by a large pommel disk. This one has a tang nut, to which an eyelet with a wrist strap would originally have been attached. The swelling grip joins the short guard and the langet in forming a cruciform shape. The entire hilt, which is made of iron, is inlaid with flowers, stems and leaves as well as carefully delimited lines of gilt copper raised in relatively high relief. Some tulwars also feature protective hand guards. Stylistically, the hilt appears older than the blade. Replacing parts of sabres and daggers over time or reusing old ones was a common practice.

Published in

Published in

Bruun Rasmussen, Asian and Islamic Art, auktion 905, 1.december 2021, lot 287;

Joachim Meyer, Rasmus Bech Olsen and Peter Wandel: Beyond words: calligraphy from the World of Islam, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2024, figs. 57 and 58, pp. 86-87;

Joachim Meyer, Rasmus Bech Olsen and Peter Wandel: Beyond words: calligraphy from the World of Islam, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2024, figs. 57 and 58, pp. 86-87;

Footnotes

Footnotes

1.

Bernd Augustin: ‘Persische Blumen erblühen in Indien: Das Werk des Muhammad Baqir Maschhadi: Klingen- und Goldschmiedekunst in Delhi unter Safdar Jang Bahadur’, Indo-Asiatische Zeitschrift, 13, 2009 pp. 99 – 121 and Kjeld von Folsach, Joachim Meyer, Peter Wandel: Fighting, Hunting, Impressing Arms and Armour from the Islamic World 1500–1850, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2021, cat. 29.

Metalwork, Weapons and Jewelry

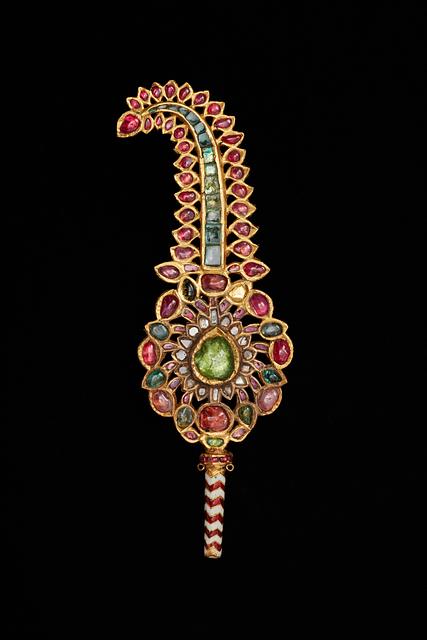

Turban ornament, gold set with rubies, diamonds, and emeralds; enameled back

Dagger (khanjarli) of steel, gold, silver, elephant ivory and rubies with sheath of wood, textile and silver

_The-David-Collection_Copenhagen_photo-Nicholas-Moss.jpg)

Water pipe (huqqa), gilded silver inlaid with enamel

Hand basin, parcel-gilt, embossed silver inlaid with blue, green, and crimson enamel